Anatomy of the Eye: Eye Structure & More

Home / Vision Education Center /

Last Updated:

The eye is a remarkable but fragile organ that allows us to see, barring injury, disease, or developmental problems. It takes in light and converts that light into a signal our brains can understand.

Table of Contents

The eye has many parts that work together to provide you with vision. It consists of the systems needed for the eye to take care of itself (again, barring serious damage) and the ability to move to look at what you want to see.

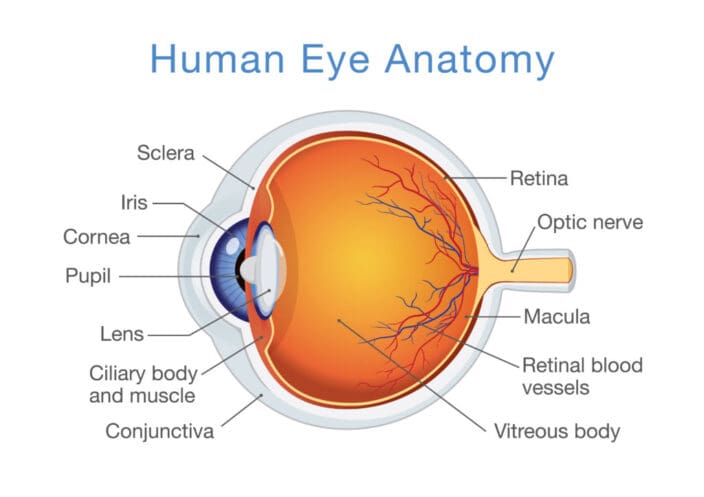

To see, our cornea refracts incoming light, with the iris controlling the size of the pupil to optimize incoming light as needed. The lens of the eye focuses that light onto the retina, which is covered with a series of special photoreceptor cells that turn that light into signals. These electrical signals are sent via the optic nerve to the brain’s visual cortex, where the brain then turns those signals into what we see.

Since doctors and scientists understand the eye fairly well, there is some hope we could one day fully build our own device to interface with the brain in the same way. This could allow us to essentially cure blindness. While some bionic eyes can give people with certain types of blindness very limited vision back, not unlike seeing flashing lights where objects and movement are, we are a long way from sci-fi cybernetic eyes.

Further study of the eye will improve our understanding of it and how it sends signals to our brain. As we learn more about it, doctors will be able to help a wider pool of people suffering from various vision problems.

The Eye

Eyes are obviously key to our sense of sight. Unfortunately, the eyes are also some of our most fragile organs. A shard of debris, untreated disease, or any number of things, including age, can damage our eyes permanently, sometimes even making us blind.

The Anatomy of the Eye

There are many parts to the eye.

You deserve clear vision. We can help.

With 135+ locations and over 2.5 million procedures performed, our board-certified eye surgeons deliver results you can trust.

Your journey to better vision starts here.

- Anterior chamber: This is the front portion of the eye, where aqueous humor flows in and out.

- Aqueous humor: This is the clear liquid inside the front part of the eye. It nourishes the eye and keeps it inflated. Roughly equal amounts flow into and out of the eye.

- Choroid: This membrane is between the retina and sclera. It contains blood vessels, and it supplies blood to the outer portion of the retina.

- Ciliary body: This multipart structure in the eye is responsible for producing aqueous humor and focusing the lens of the eye.

- Cornea: This is one of the most important parts of the eye. It is the dome-shaped surface on the front of the eye that helps to focus light. It provides visual sharpness and clarity.

- Fovea: The center of the macula, this part is key to sharp vision.

- Iris: The colored portion of the eye, the iris regulates how much light gets into the eye.

- Lens (or crystalline lens): This clear structure is inside the eye and focuses light. It can be replaced if necessary, as it naturally deteriorates with age.

- Macula: This portion of the retina contains special light-sensitive cells that allow us to see details. This is another area prone to deterioration as we age.

- Optic nerve: This is a bundle of over 1 million nerve fibers that links the retina with the brain. The optic nerve connects the eye to the brain’s visual cortex. Without this connection, you would be blind even if the rest of the eye worked entirely as intended. Interestingly, your retina actually sees images upside down, but your brain then flips them.

- Pupil: This is the dark opening in the middle of the iris, The pupil works like an aperture, adjusting based on the amount of light in an area. This allows you to see well without taking in too much light that could damage the eye or distort vision.

- Retina: This nerve layer lines the inside of the back of the eye. It senses light and creates an electrical impulse that is then sent through the optic nerve.

- Suspensory ligament of lens: This is a series of fibers that link the ciliary body of the eye with the lens. It holds the eye in place.

- Sclera: This is the white visible portion of the eye. The muscles that move your eye connect to the sclera.

- Vitreous body: This is the clear, gelatinous substance in the back part of the eye.

While the eye is not totally incapable of healing from damage, it is a relatively delicate system. If a part that is essential to vision is damaged by trauma or disease, it may not necessarily lead to permanent blindness, but it will usually have a serious impact on vision.

The eye is also very sensitive to pain — to help the body protect it. This makes eye injuries often disproportionately painful even if the damage itself is not serious.

How Do We See?

To see, light first passes through the cornea. The cornea refracts this incoming light. The iris controls the size of the pupil, so the correct amount of light can enter the eye.

The lens then focuses that light onto the retina. The retina’s photoreceptor cells convert the light into electrical signals, which are then sent via the optic nerve to the brain.

Everything we see is just light bouncing off objects, converted to an electrical signal, and then interpreted by our brain as an image (barring medical conditions that interfere with this process in some way). There are many colors to light, with the color of something determined by what wavelength of light we see bouncing of it. Our eyes can only see what is known as the visible spectrum of light.

To make a complicated field of science as simple as possible, the reason something is whatever series of colors it appears to be is controlled largely by two things. The first is how much light is able to bounce off it and be interpreted by our eye (and what color that light is since not all light is a perfect white). The second is how that object’s materials interacts with that light hitting it, thus changing the wavelength of light’s speed as it bounces and therefore the color our brain will see.

How to Protect Your Eyes

Eating healthy, exercising, avoiding smoking and having regular eye exams can help you preserve your vision as you get older. You can also take simple everyday measures to protect your eyes from harm, including:

- Guard your eyes against sun damage by wearing protective sunglasses every time you leave the house. Consider getting eyewear with nearly 100% anti-UVA and anti-UVB protection.

- Wear appropriate safety glasses at work or in certain sports, including welding, construction work, and swimming.

- To alleviate eye strain when working at a computer, take your eyes off the screen every 20 minutes and fixate on an object 20 feet away for 20 seconds.

- Handle your contact lenses with clean hands and replace and disinfect them regularly to avoid introducing bacteria into your eyes.

Most Fragile Parts of the Eye

To preserve your vision for as long as possible, you should protect all parts of your eyes. All of them are delicate.

The cornea is one of the most sensitive parts of the eye because of its many nerve endings. Its high sensitivity to scratches, dust, heat or pathogens ensures appropriate responses, such as tearing and blinking, to protect the eye’s surface.

Even so, vision-threatening injuries or conditions can affect other parts of the eye. For instance:

- Glaucoma affects the optic nerve

- Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) affects the macula

- An irregularly shaped cornea causes blurred vision

- Diabetes can affect the retina

- Cataracts form around the lens

You deserve clear vision. We can help.

With 135+ locations and over 2.5 million procedures performed, our board-certified eye surgeons deliver results you can trust.

Your journey to better vision starts here.

How Long Should Vision Last?

It’s possible to maintain excellent eyesight throughout your lifetime. But it’s not a given.

Just like any other body organ, eyes lose some visual power as you get older. It may reach a time when you can’t read or properly focus on distant objects without prescription glasses, especially beyond the age of 40.

Some people may even have trouble differentiating colors. These are normal age-related issues that can affect anyone.

However, vision loss isn’t a normal part of aging. Some of the common eye diseases or conditions that damage eyesight are preventable, and certainly manageable, if detected early.

Your vision can last your lifetime if you prevent or treat complications such as glaucoma, cataracts and diabetic retinopathy.

Can We Build Our Own Eye?

Obviously, human have figured out how to record images. We can produce photographs and video in a myriad of ways. Additionally, we understand a great deal more about the eye than our ancestors did. We can explain, in a fair bit of detail, how it works.

For a while now, many have pursued a way to combine technology with the body, in the hopes of creating a man-made eye that works much in the same way as our natural eye. The sci-fi ideal of a cybernetic eye producing a quality of vision even better than our natural vision is a long way off, if it is possible at all.

The brain is a very complicated organ that is not fully understood. Finding a way to make it properly interface with any camera technology at all is a monumental task.

At the same time, there are devices that can be put into eyes that do allow some people with very specific conditions to “see,” but the detail comes purely in flashing lights with low visual detail presently. Even these devices can dramatically improve a user’s mobility and ability to interpret obstacles and objects. As the technology is improved and researched, it is an exciting field that holds much promise.

Always Worth Further Study

The complexity of the eye, how it takes in light, and how the brain interprets its signals are things we certainly know a great deal about, yet there is clearly an astronomical amount more to be learned. The more clearly the eye and visual cortex of the brain are understood, the better we can help people with vision problems.

The ideal is a future where even those born blind or who lose eyes can eventually see.

You deserve clear vision. We can help.

With 135+ locations and over 2.5 million procedures performed, our board-certified eye surgeons deliver results you can trust.

Your journey to better vision starts here.

References

- Anatomy of the Eye. University of Michigan.

- Anatomy of the Eye. The Johns Hopkins University.

- 5 Industries Where Eye Protection Is a Priority. Bollé Safety.

- How We See. National Eye Institute.

- Aqueous Humor. (January 28, 2019). American Academy of Ophthalmology.

- Colours of Light. (April 4, 2012). Science Learning Hub.

- Artificial Vision: What People with Bionic Eyes See. (August 16, 2017). The Conversation.

This content is for informational purposes only. It may have been reviewed by a licensed physician, but is not intended to serve as a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult your healthcare provider with any health concerns. For more, read our Privacy Policy and Editorial Policy.