Neurological Disorders and Eyesight

Home /

Last Updated:

You may understand nearsightedness, farsightedness, and other common eye conditions. You know they stem from the anatomy of your eye, paired with lifestyle choices and potential injuries.

But did you know your vision also relies on a delicate network of brain cells and nerves? If those are damaged, you can develop vision issues, and some are severe.

Table of Contents

In this guide, we’ll discuss common neurological conditions that can harm your eyesight, including:

- Optic neuritis. This condition involves swelling of the optic nerve, and it’s common in people with multiple sclerosis.

- Ischemic optic neuropathy. This develops when the optic nerve is starved of blood flow. It can develop alongside heart disease, and the damage done can be permanent.

- Primary open-angle glaucoma. Your eye needs to drain the tears you produce. When that does not happen, pressure builds. That can lead to pressing on the optic nerve, which can harm it and lead to vision loss.

- Parkinson’s disease. This condition impedes your ability to both move and control your muscles. That can impair your ability to blink and move your eyes. You may also struggle with color perception.

- Blurred vision is a sign of stroke, but if you have one, you can be left with vision difficulties involving depth perception and visual understanding. Some of these changes are permanent.

Optic Neuritis: An Inflamed Optic Nerve

Your optic nerve works like a sight highway. Signals move from the eye to the brain down this path, and it’s that movement that helps you to see clearly. Swelling in the optic nerve (optic neuritis) can slow or even block those messages.

Optic neuritis is closely related to multiple sclerosis (MS). This condition causes nerves all around the body to swell, and researchers say about a third of people with MS do not know they have the condition until they develop optic neuritis.

You deserve clear vision. We can help.

With 135+ locations and over 2.5 million procedures performed, our board-certified eye surgeons deliver results you can trust.

Your journey to better vision starts here.

It’s also been associated with risks such as:

- Infections. Lyme disease, syphilis, cat-scratch fever, and bacterial invasions can all cause the optic nerve to swell.

- Viruses. Herpes, mumps, and measles can cause optic neuritis.

- Medications. Some types of antibiotics and the drug quinine can cause swelling in the optic nerve.

Optic neuritis usually attacks one eye while leaving the other intact, says Mayo Clinic. You might notice:

- Vision loss. Some people develop a slight blurring or dimming of vision, while other people can’t see anything at all. Some people retain clear central vision, but can’t see anything to the side.

- Visual hallucinations. You may see flashing or flickering lights. Colors might seem dim or dull.

- Eye pain. You might develop a headache, and it can get worse when you move your eyes.

Your eye doctor can diagnose optic neuritis through an eye exam. Your doctor will measure your response to bright light and your ability to differentiate colors. Your doctor might also test your vision and examine the back of your eye. An MRI may help to formalize the diagnosis.

If you do have optic neuritis, treatment helps. Your doctor can use corticosteroids to reduce swelling in the nerve. According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology, some people experience a full recovery with this medication.

It’s critical for you to see your doctor if you think you have optic neuritis, as it’s a very serious condition that can worsen without treatment. And if it is the first sign of multiple sclerosis, that is important for you to know.

MS is a degenerative disease that requires medical management. The earlier you get help for that issue, the better.

Ischemic Optic Neuropathy: When Nerves Need Blood

Your nerves are conduits for messengers, and they require a lot of blood to do their work. If you’ve ever sat with your crossed legs for too long and felt pins and needles take hold, you know this firsthand.

When nerves do not get the blood they need, bad things happen. When the optic nerve is starved of blood flow, it’s called ischemic optic neuropathy, and it can permanently damage vision.

Several types of blood vessels support and nourish the optic nerve. Each can fail in a different way. In general, researchers recognize two main forms of ischemic optic neuropathy (ION).

- Anterior ION: A lack of blood flow causes the optic nerve head to swell.

- Posterior ION: Blood flow remains a problem, but there is no swelling.

Both conditions are eye emergencies, and if you have them, you need immediate treatment.

You will develop sudden vision loss in one or both eyes, and you will not feel pain. During an exam, your doctor might notice that your pupils are not responding to light, and your optic nerve might look unusual.

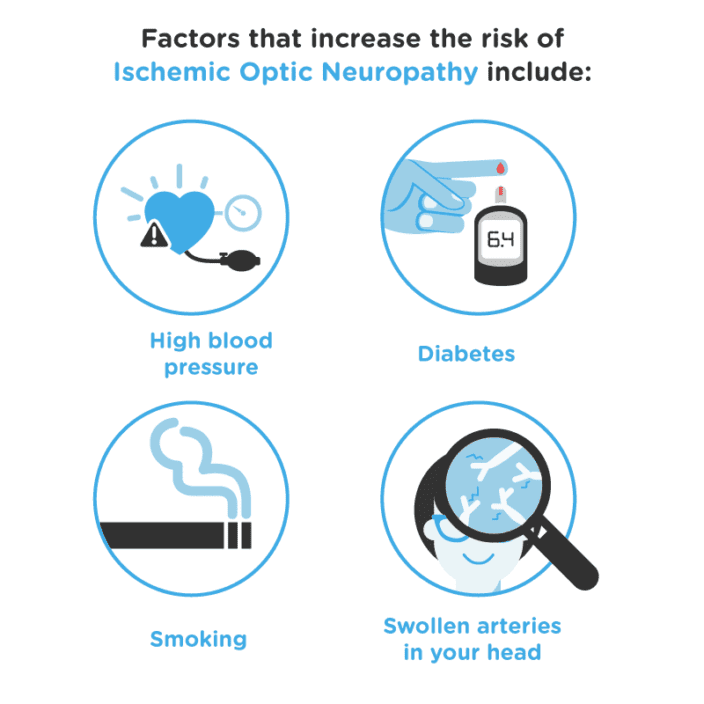

Since ION is a disease of the blood vessels, and damage to the eyes is a side effect of that damage, you are at higher risk of the condition if you have risk factors for heart disease. Those risk factors include the following:

- High blood pressure

- Diabetes

- Smoking

- Swollen arteries in your head

Your risk also rises if you are older than 50, have glaucoma, or have a history of migraine headaches. But anyone can get ION, says the American Academy of Ophthalmology, whether you have risk factors or not.

If your doctor spots an ION, treatment might involve prednisone. This medication can reduce swelling, and that can help your optic nerve to return to its normal size. The drug could also protect your other eye if you do not have symptoms there.

Your doctor might also ask you to visit a cardiovascular expert, so you can get treatment for the risk factors that lead to this condition. You might be advised to lose weight, exercise more, and reduce your salt intake.

But the vision loss you experience with ION might persist, despite your treatment. Nerves are delicate, and when they are damaged, they do not always heal properly. If that happens, your doctor can help you understand how to compensate for the vision you’ve lost.

Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma: Rising Eye Pressure

The center of your eye is filled with a gel-like substance. It pushes precisely on the back of the eye, helping delicate nerve tissue to stay connected and communicating.

Meanwhile, the surface of your eye remains slick with tears. They should flow in and out in perfect balance. When they do not, pressure rises within the eye. That can damage sensitive tissue at the back of the eye that helps you see.

All diseases of eye pressure are glaucoma, but primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is the most common form.

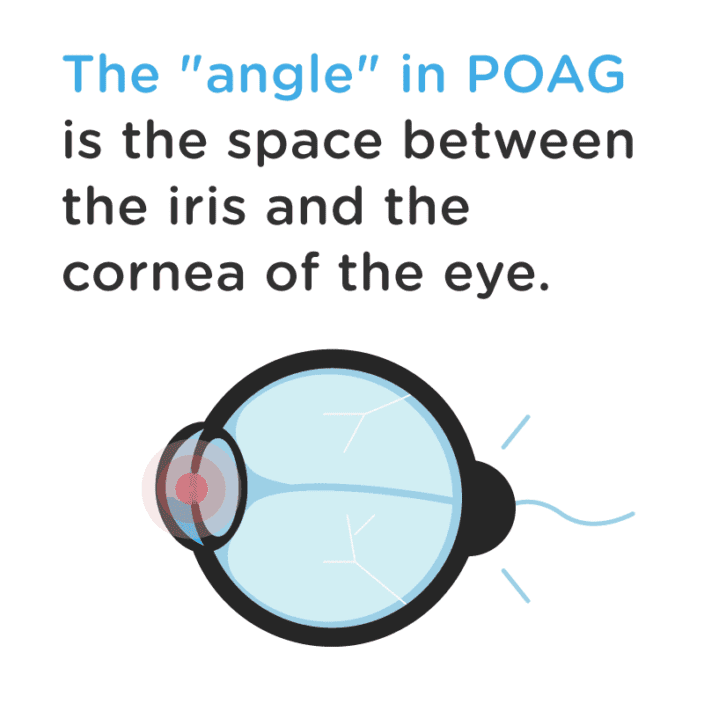

The “angle” in POAG is the space between the iris and the cornea of the eye. That is the space where fluid inside the eye drains out into your body’s circulatory system. When that system malfunctions, POAG takes hold.

The Glaucoma Foundation says about 1 percent of all Americans have POAG, but some may not know it. The condition does not cause initial symptoms that are common to other eye conditions, such as pain, sudden blindness, or visual distortions.

Often, symptoms begin in just one eye. You might have spots of blackness in your peripheral vision or a dip in visual acuity. But your other eye compensates for the loss, so you do not notice the shift.

The Bright Focus Foundation says African Americans are three to four times more likely to develop glaucoma. Other risk factors include:

- Advancing age. The condition is more likely in people older than 40, and the risks continue to rise with each birthday you celebrate.

- Family history. If a glaucoma diagnosis or nearsightedness runs in your family, you could be at higher risk.

- Type 2 diabetes. This condition can cause inflammation and nerve damage throughout your body. If those conditions impact your eye, your risk of glaucoma rises.

- Severe nearsightedness. People with extreme myopia have very long eyeballs, and they sometimes have thin corneas. Both conditions can lead to changes associated with glaucoma.

If you have risk factors for glaucoma, you should have a full visual exam every year. Your doctor can check your eye pressure and look inside your eye to assess the health of your optic nerve.

If glaucoma is found, your doctor might use one or several medications to help you get better. Laser surgery can also help, as it allows your doctor to address the source of poor eye drainage. After surgery, your eye may no longer swell, and that could reduce your need for medication management.

The vision you lose due to glaucoma can be permanent, however. When nerves are significantly damaged, they do not always heal. That is why prevention is so critical. But even if you do lose vision, your doctor can help you understand how to cope with the loss and continue to enjoy your life.

Parkinson’s Disease: Motor Control and Nerve Damage Combine

When we think of Parkinson’s disease, we think of muscles. People with the condition tend to slur their words, stumble as they walk, and jerk their arms and legs periodically.

Damage to myelin, or the nerve’s protective covering, is to blame. That allows nerves to drop or cross signals. But the condition can also interfere with vision, even if the eye itself has no muscles within it.

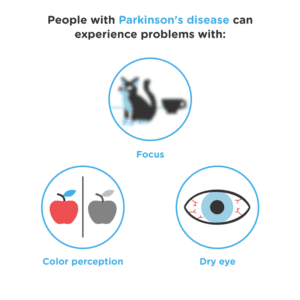

People with Parkinson’s disease can experience problems with:

- Focus. When you can’t control the muscles around your eye, it’s hard to look closely at an object. Your eyes may not look in the same direction, or they may not stay in one place for long enough.

- Color perception. The disease can kill off retina cells at the back of the eye, researchers say, and when that happens, it’s harder for you to perceive colors. Everything may appear gray, or the world may seem washed out.

- Dry eye. When muscles do not fire properly, blinking is tough. Some people with Parkinson’s disease do not blink frequently enough, and their eyes feel dry and gritty.

Parkinson’s disease can develop due to family history, but Parkinson’s News Today suggests that risk can rise due to:

- Head injuries. When you have a blow to the head, your body responds with swelling. It’s meant to keep broken parts still and in place, but it can put great pressure on your nerves. Parkinson’s risk rises in the months or years after the event.

- Toxin exposure. Herbicides, fungicides, and insecticides can harm your nerves, and that can lead to Parkinson’s disease.

- Age. The condition typically develops in people in middle age.

Your eye health may not prompt you to ask a doctor about Parkinson’s disease. But the subtle trouble you have with blinking and focusing could be early indicators of the condition. Your doctor may diagnose the problem during a routine eye exam, or you might be encouraged to go to a neurologist for more testing if you are at risk for Parkinson’s and your eyes bother you.

There is no cure for Parkinson’s disease, says the American Parkinson Disease Association. But some treatments can ease your symptoms. Your doctor might use:

- Medications to give you control over muscle movement.

- Physical therapy to smooth your movements and build muscle.

- Occupational therapy to help you handle daily tasks with ease.

- Speech therapy to help you speak clearly or find alternate ways to communicate.

Your doctor may choose eye drops to keep the eyes moist. And special glasses may help you focus your attention, so you can read and handle other tasks without disruption.

You deserve clear vision. We can help.

With 135+ locations and over 2.5 million procedures performed, our board-certified eye surgeons deliver results you can trust.

Your journey to better vision starts here.

Alzheimer’s Disease: Multifaceted Vision Changes

When it comes to chronic conditions, we know the least about Alzheimer’s disease.

Researchers discovered the condition in the 1980s. Since then, they’ve been working hard to understand how the problem begins and what can be done to treat it. They do know that people with the condition have changes in visual ability, but no one is quite sure why.

The Alzheimer’s Association says 5.7 million people lived with the condition in 2018, and that number should rise as the population ages. Most people with Alzheimer’s are identified due to severe memory loss and functional brain changes. They may forget words, get lost, or experience unusual emotional shifts.

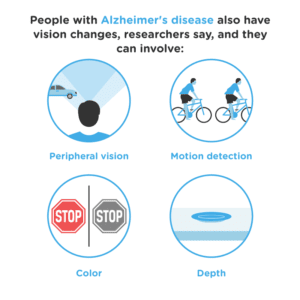

People with Alzheimer’s disease also have vision changes, researchers say, and they can involve:

- Peripheral vision. When the field of vision shrinks, you are only able to see the things right in front of you, unless you move your head. You may find that you run into things often, or you may fall.

- Motion detection. You may see the world as a series of still photographs, and that can cause you to get lost in familiar spaces.

- Color. You may struggle to identify colors, or the whole world may seem dim and gray.

- Depth. Everything may seem flat to you, and that can make it hard for you to spot items you need, like a plate on the table.

Vision changes with age, and since people with Alzheimer’s disease are often older, it’s easy to chalk up these changes to a natural part of the aging process. But some researchers suspect that Alzheimer’s disease can alter communication paths between the optic nerve and the brain. People may be able to see clearly, but the messages get scrambled as they move to the brain.

More research can confirm this hypothesis, and right now, it’s a guess.

If you do have Alzheimer’s disease, your treatment might involve cholinesterase inhibitors. As the Alzheimer’s Association explains, these drugs help to boost chemical signals the brain needs to learn and retain memories. They can’t amend symptoms you already have, but they could keep the condition from worsening.

Alzheimer’s disease is progressive, and you will need to take steps to protect your safety. You may need brighter carpet and furniture, so you can see where one object begins and another ends. And you may need to install bumpers on sharp corners, so you do not get hurt as you walk.

Stroke: Brain Clots Change Vision

You may know that double vision is one symptom of a stroke. And you may know that strokes are incredibly common, as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says someone has a stroke in the United States every 40 seconds. But you may not know that living through a stroke can change your vision permanently.

A stroke stems from a blood clot within the brain. It plugs vital blood from moving to the cells that need it, and they begin to die. If your stroke is centered on the portion of the brain responsible for vision and image processing, you may be left with deficits from the cells that died during your stroke.

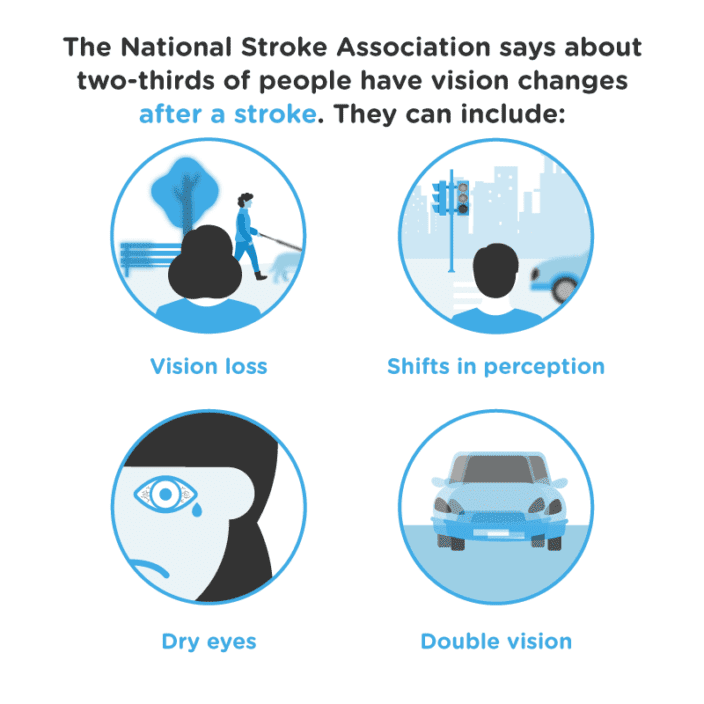

The National Stroke Association says about two-thirds of people have vision changes after a stroke. They can include:

- Vision loss. You may have gaps in the center or side of your visual field, and they will vary in size depending on the severity of the damage done.

- Shifts in perception. You may struggle to see and understand depth and colors. You may not recognize items you once knew well. And you may find it hard to focus on items on one side of your body.

- Dry eyes. Blinking can be difficult, and without a layer of tears, the surface of your eye can dry and harden.

- Double vision. You may see two of the same item, even when only one is present.

Strokes move quickly, but medications can help to soften the clot and ease the damage you will endure during the episode. If you are given quick treatment and the damage is minor, your brain may heal.

Brain cells can knit together new connections, and when they do, they can begin to transmit signals from the optic nerve to processing centers as intended. But there is a limit to your healing. Within a few months of your stroke, you might see improvements. But after that time, you may not.

Your doctor can help you adjust to vision changes after a stroke. Glasses, including some with patches of high magnification, could help you overcome vision difficulties. Your doctor can also teach you how to scan your visual field, so you can use the entirety of your eye despite the damaged portions.

Moving Through Eye Challenges

Reading about disorders like this is not easy, especially when many of them cause permanent damage. It’s important to understand that you do not have to take on these challenges alone.

Opticians, ophthalmologists, and other eye experts are adept at both examining eyes and developing treatments for deficits. A visit to an expert like this could result in solutions you would never have thought of on your own.

And a relationship with an eye doctor could help you to prevent some of these issues from ever developing, so you can preserve your vision throughout your life.

If you do not have an expert on your side now, it’s time to start searching.

You deserve clear vision. We can help.

With 135+ locations and over 2.5 million procedures performed, our board-certified eye surgeons deliver results you can trust.

Your journey to better vision starts here.

References

- Neurologic Disorders Have Varied Ocular Symptoms. (July 2006). Ocular Surgery News.

- Optic Neuritis. (November 2016). Mayo Clinic.

- Optic Neuritis. Columbia University Department of Neurology.

- Optic Neuritis Treatment. (June 2019). American Academy of Ophthalmology.

- Diagnosing and Managing Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. (October 2010). Review of Ophthalmology.

- Who Is at Risk for Getting ION? (May 2019). American Academy of Ophthalmology.

- Ischemic Optic Neuropathy (ION) Treatment. (May 2019). American Academy of Ophthalmology.

- Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma. (December 2018). Glaucoma Research Foundation.

- Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma (POAG). The Glaucoma Foundation.

- Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma (POAG). (March 2019). Medscape.

- Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma. (October 2017). Bright Focus Foundation.

- What Causes Parkinson’s Disease? Parkinson’s News Today.

This content is for informational purposes only. It may have been reviewed by a licensed physician, but is not intended to serve as a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult your healthcare provider with any health concerns. For more, read our Privacy Policy and Editorial Policy.